Orchestrophonia

for Mechanical Musical Instruments and Orchestraby Norman Lowrey

Program Notes

-PLAY-

Reviews:

Newark Star Ledger | Recorder Community Newspapers | Classical New Jersey

Mechanical, but original

Orchestra and museum pieces make beautiful music together

Monday, May 14, 2007

BY BEN FINANE

For the Newark Star-Ledger

CLASSICAL

Saturday night's concert by the Colonial Symphony at Morristown's Community Theatre featured a delightful world premiere that married orchestral music with music produced by mechanical instruments, all thanks to a curious collaboration between a conductor, a composer and a museum.

The project took root when maestro Paul Hostetter, music director of the Colonial Symphony, visited Morristown's Morris Museum and was inspired by the Murtogh D. Guinness Collection of mechanical instruments, which have been on display since late 2003.

The exhibit, unique to the Western Hemisphere, features music boxes, mechanical instruments and automata (mechanical figures) built in the 19th century, used largely by wealthy Europeans as parlor entertainment before the rise of the recording industry. There are 700 pieces in the collection, 60 of which are currently on display, and the museum is currently constructing a new wing (set to open this November) in order to showcase more.

Following Hostetter's visit to the museum, the Colonial Symphony commissioned composer Norman Lowrey to create a work that would achieve, in the words of Hostetter, "true collaboration" between the mechanical instruments and the orchestral players.

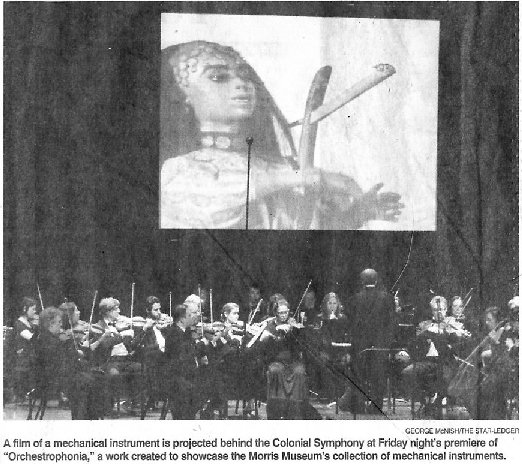

Lowrey, who chairs the music department at Drew University, visited the museum's collection and decided that the large size and fragility of the instruments rendered their use on stage impractical at best. Instead, Lowrey created a film of the instruments in action and then wrote music for orchestra to be played along with that of the mechanical instruments. At Friday night's premiere of Orchestrophonia, the film was projected on a screen behind the orchestra in 5.1 surround sound and two "live" music boxes from the museum's collection joined the orchestra.

Orchestrophonia unequivocally achieves the spirit of collaboration that Hostetter had hoped for between orchestral and mechanical instruments, primarily because the latter are treated as musical equals. The piece is not so much a concerto as an homage to these instruments, which, long silent, are able to share their tunes once more.

Lowrey's orchestral writing supports the tone of each of the featured mechanical instruments, which range from nostalgic to carnivalesque to Sgt. Pepper-esque. The ideas and tunes are of course literally expanded, but the songs also overlap, creating not so much a soundscape as a gentle dreamscape. The result is a commendable and thoughtful piece.

Operating under the precept that the fusing of mechanical and orchestral instruments is revolutionary, the Colonial Symphony bookended the premiere with two other revolutionary works by masters of musical innovation: Wagner's Siegfried Idyll and Beethoven's Fifth (Symphony). Hostetter's account of the Wagner was gentle if sleepy, but his economical Fifth was a crisp delight.

By no means workmanlike, Hostetter let Beethoven do the talking and did not burden the listener with added schmaltz posing as artistic feeling. The interpretation was enhanced by the clean sound and relatively small size of the Colonial Symphony, which permitted a glimpse into the inner workings of what can be a loud and proud warhorse.

Turning to Steven Miller, executive director of the Morris Museum, Hostetter said in his pre-concert lecture, "I believe in the inherent value of these instruments."

The deliberate cadence and fist-pumping that accompanied this statement would have elicited a quiet chuckle from Bill Clinton, but the successful premiere showed that Hostetter wasn't just playing politics.

(See reviews: Newark Star Ledger, Recorder Community Newspapers, Classical New Jersey)

BACKnlowrey@drew.edu